In 1978, I was an associate editor of The Catholic Worker newspaper when a review copy of a new book, Confessions of a Catholic Worker by Michael Garvey arrived in the mail. Dorothy Day, the paper’s publisher, waved it off dismissively, saying “I hope that it is HIS confessions, not mine!”

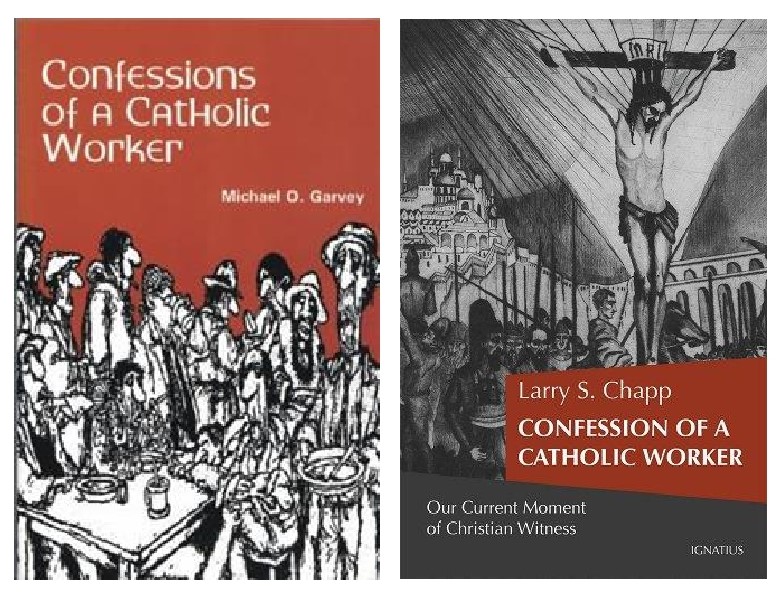

Already hailed as a living saint, Day was not so unworldly as to be unaware of a whole popular genre of such “confessions,” tell-all exposés each more salacious then the last, beginning with Confessions of a Window Cleaner in 1974 (“Tim becomes a window cleaner, with the help of Sid, and is told to work until he fully ‘satisfies’ all his customers”) that was reaching its peak about that time. She might have also recognized the stark pen and ink rendition of a soup line on the book’s cover as work of the popular artist Rodrigues, best known for his cartoons in Playboy and The National Lampoon magazines.

As if anticipating Day’s reaction, Garvey quotes from The Early Martyrs by Mrs. Pope, “The accounts of this vision which reached Constantine cheered him a little, but still he continued to be very anxious,” on the dedication page of his book.

More than an effective marketing ploy, the book’s title and cover art informed the reader from the start that Confessions of a Catholic Worker was not a pious exaltation of Day or the movement that she and Peter Maurin founded forty-five years before. Not a hagiography or theological study, it is a collection of stories from the daily life at the Catholic Worker house in Davenport, Iowa. If Garvey’s introductory assertion that “everything described here has actually happened” may itself be an exaggeration, the book rings true and has become a classic of Catholic Worker literature. Michael Garvey died last year and I would love to see another edition of his Confessions as a tribute to him.

Mostly a book of stories, Garvey did insert his own opinions here and there. The most helpful for us today in the movement’s present condition is his warning in 1978, two years before she died, “A square halo is at this moment threatening Dorothy Day and the entire Catholic Worker movement, and I think that it would be a disastrous blow.” In early Christian iconography, he informs us, “the square halo would be placed over the head of a person the faithful were impatient to exalt… but who hasn’t gotten around to death and canonization as yet.” “One of the important challenges to which the movement gives witness is the accessibility and ordinariness of the sort of life it requires,” Garvey insisted. “A great deal of the beauty of Peter Maurin’s vision of a new society within the shell of the old is its aspect of being no big deal.”

A few months after the release of Garvey’s Confessions of a Catholic Worker, I left the Catholic Worker in New York for the house in Davenport, where I stayed for the next seven years.

Forty-five years after Garvey’s Confessions, as if to confirm his square halo fears, comes the publication of a new book with a similar title, Confession of a Catholic Worker: Our Moment of Christian Witness, by Larry S. Chapp. The cover art of Chapp’s Confession is a drypoint etching of the crucifixion by Lodewijk Schelfout. Like the cartoon that adorns Garvey’s Confessions, it tells a lot about the book’s contents- this Confession, unlike the other, is a hagiography and a theological study, relieved by very few stories. It is a pious exaltation of Day and the movement that she and Maurin founded, ninety years ago now. The authors of both Confessions admit an aversion to the presence of felt banners in church, but the similarity stops there.

“This is not a book ‘about’ Hans Ur von Balthasar, Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, or the Catholic Worker movement in general,” Chapp insists. “This is a book inspired by them and formed within the thought-world that they have created within me.” If Day’s fears that Garvey’s confessions might have actually been hers was unfounded, Chapp’s Confession does seem to cross that line as he presumes to project his positions and that of other theologians onto Day and Maurin.

Chapp refers to “Balthasar, Day and Maurin” together over and over in his Confession, as if the agreements among them were too obvious to cite. Chapp quotes extensively from Balthasar and other theologians of that ilk, but he offers no indication from Day or Maurin why he thinks that they might agree. Day and Maurin have no voice in the matter. The reader needs to take Chapp’s word on it. Day was a contemporary of Balthasar and was well informed and active, even travelling to Rome to petition for a condemnation of nuclear weapons from the Second Vatican Council- Day certainly knew of Balthasar, but never, it seems, thought enough about him to mention.

Chapp cites a “bombshell” of an article by Joseph Ratzinger, later to be Pope Benedict XVI, from 1958, called “the New Heathens and the Church.” He suggests that Ratzinger’s “blunt analysis” was “radically similar to that of Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day.” A quick reading of the article does not immediately reveal a similarity, radical or otherwise, except that it causes me to wonder if Maurin and Day were not among the “new heathens” that caused young Joseph Ratzinger such alarm.

Curiously, Chapp does briefly recognize the one theologian of the era who did influence Day, Romano Guardini, but without citing his maxim that she so often repeated: “the Church is the Cross on which Christ is always crucified. One cannot separate Christ from his bloody, painful Church. One must live in a state of permanent dissatisfaction with the Church.”

Missing from this Confession, too, is any indication of the social encyclicals that inspired and formed Day and Maurin but not so much, it seems, Chapp and Balthasar. Pope Francis’ recent encyclicals that inspire many Catholic Workers and others to actions to defend the earth do not get a mention, either.

While he admits the existence of Day’s “wealth of writings,” Chapp does not avail himself of them and her voice is only heard in his raising of the (dubious) “don’t call me a saint” quote. Peter Maurin comes off a little better, as Chapp quotes Maurin’s signature Easy Essay, “Blowing Up the Dynamite of the Church” without recognizing how readily Maurin’s criticism might apply to the works of Balthasar, Ratzinger or even to Confession of a Catholic Worker by Larry S. Chapp:

“If the Catholic Church

is not today

the dominant social force,

it is because Catholic scholars

have taken the dynamite

of the Church,

have wrapped it up

in nice phraseology,

placed it in a hermetic container and sat on the lid.”

After quoting Maurin, Chapp gets out of his thought-world and devotes a few paragraphs to what he is actually doing at his farm in Pennsylvania, about local economics and even celebrating teaching a child how to milk a goat (Go, brother Larry!) The respite is welcome, but all too brief and spoiled by his undisguised contempt for others devoted to the same life and work.

Chapp uniquely identifies himself as “owner and manager” of a Catholic Worker farm, a title that evokes the plantation, the feudal manor or corporate agribusiness more than it does the green revolution that Maurin preached. From this vantage of authority, Chapp pronounces judgement: “The vision of Peter Maurin in particular is deeply in line with that of Balthasar” and “without a recovery of his vision, the ongoing viability of Catholic Worker farms as specifically Catholic projects is gravely in doubt. And if their Catholicity is in doubt, then their very existence is also in doubt, since trendy ‘back to the land’ hippy communes always crash and burn, due in large part to the fact that the sinful entropy of our selfishness is always stronger than cannabis fueled free love.”

Day was more optimistic, more generous and had a more universal vision than Chapp. In 1975, she referenced the “encouraging words” of the Black activist, comedian (and non-Catholic) Dick Gregory, whom she elsewhere commends as a living saint,

“which I recognize as true, is the fact that radical youth on all sides of us… are becoming personalists, making the beginning of a truly ‘personalist and communitarian’ revolution, which is based on voluntary poverty and manual labor….there is a strong, vital healthy movement among the young in many parts of the country. They are getting back to the land, emphasizing voluntary poverty, manual labor, the crafts, getting a piece of land near others, clearing it and making a start. If they want the cash for tools, etc., they have to take any odd job and earn it. If they want shelter, they have to cut logs for cabins and build them. We are seeing plenty of this activity in the Catholic Worker movement, and among Peacemakers and other groups. It makes the heart rejoice and fill with hope, and even though it seems that wars will never end, and suffering will never cease, man will not give up hope.”

While Day had the concern for the morals of the young that many older people have, she did not share the disdain exhibited in the above mentioned “cannabis fueled free love” crack. In August, 1969, Day recorded in her diary, “Story in Times about Rock Festival at Bethel (Woodstock), most favorable. ‘A well behaved half million young people.’ All farm teenagers went.” Later she reported from Mass at the local church in Tivoli, “A good sermon but ending with condemnation and ill-disguised disgust at the youth ‘orgy of sex and drugs’ at Bethel. No compassion for the young.”

Unlike Chapp’s theologians, Day did not believe that a Catholic or Christian profession of faith were necessary to serve Christ. If Day were not one of Ratzinger’s “new heathens,” her friends certainly were. In her biography From Union Square to Rome she wrote,

“Better let it be said that I found Him through His poor, and in a moment of joy I turned to Him. I have said, sometimes flippantly, that the mass of bourgeois smug Christians who denied Christ in His poor made me turn to Communism, and that it was the Communists and working with them that made me turn to God.”

Day’s radicalism did not grow from her Catholic faith, as Chapp and others insist- her Catholic faith grew from her radicalism. While Day and Balthasar both spoke of a universal call to holiness, they each meant different if not opposed things- for Day, the “synthesis” she cried out for, “the saint-revolutionist who would impel by his example, others to holiness,” was not necessarily Christian, much less Catholic.

In that same chapter of From Union Square to Rome, Day quoted the novelist Françoise Mauriac, “What glorious hope! There are all those who will discover that their neighbor is Jesus himself, although they belong to the mass of those who do not know Christ or who have forgotten Him. And nevertheless, they will find themselves well loved. It is impossible for any one of those who has real charity in his heart not to serve Christ. Even some of those who think they hate Him, have consecrated their lives to Him; for Jesus is disguised and masked in the midst of men, hidden among the poor, among the sick, among prisoners, among strangers. Many who serve Him officially have never known who He was, and many who do not even know His name, will hear on the last day the words that open to them the gates of joy. O Those children were I, and I those working men. I wept on the hospital bed. I was that murderer in his cell whom you consoled.’”

(Charitably, Day does not extend the quote to include Mauriac’s warning that many who claim Christ name and who profess to serve Him will, upon judgement, hear the terrible words “go away, I never knew you!”)

Much has been written lately to disassociate Day from her secular anarchist comrades in ways that contradict her life story and her own words. Chapp’s insistence that “Dorothy’s anarchism was rooted in the Catholic vision of social subsidiarity” is challenged by Day’s report from an anarchist’s conference she attended in 1974:

“I did not ‘talk Jesus’ to the anarchists… Because I have been behind bars in police stations, houses of detention, jails and prison farms, whatsoever they are called, eleven times, and have refused to pay Federal income taxes and have never voted, they accept me as an anarchist. And I in turn, can see Christ in them even though they deny Him, because they are giving themselves to working for a better social order for the wretched of the earth.”

Chapp points out, what Maurin and Day “understood is that now is the moment of the laity, just as Vatican II observed as well.” He got that right, but Day’s understanding of this fact was not the same as his. In her 1964 eulogy to her atheist friend Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Secretary General of the Communist Party, USA, Day wrote:

“as the Ecumenical Council has stressed, this is the age of the laity…in the widest sense of the word, Gurley Flynn was of the laity, and she was also my sister in this deep sense of the word. She always did what the laity is nowadays urged to do. She felt a responsibility to do all in her power in defense of the poor, to protect them against injustice and destitution.”

Chapp’s conviction that a society based on a profession of faith in Christ will be a more just and peaceful one is obviously not borne out in history. “It wasn’t a priest who weaponized nuclear energy and then incinerated, in a huge war crime of indiscriminate slaughter, two hundred thousand Japanese city dwellers,” Chapp says. It gave no to comfort Fr. George Zabelka, the repentant chaplain to the US Army Air Corps bomber crew that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, that the crime was committed as Chapp believes, by “the secular American government to achieve purely secular aims.” Brainwashed at the time, Fr. Zabelka believed and counseled those souls in his charge that dropping the bomb was in the service of God. In 1945, most American Catholics, Day being one of the few exceptions, agreed.

In 1967, in reply to Cardinal Spellman’s support of the Vietnam war, “my country right or wrong” he said, Day responded:

“But what words are those he spoke – going against even the Pope, calling for victory, total victory? Words are as strong and powerful as bombs, as napalm. How much the government counts on those words, pays for those words to exalt our own way of life, to build up fear of the enemy.”

As a Catholic, Day would never have countenanced such a cheap and self-serving protestation of Catholic innocence. A good Confession requires a better examination of conscience.

“Our Church and our culture are at an important crossroads,” Chapp says. “If you do not share the view that we are in a unique and decisive moment, then what I am saying here will probably not speak to you. You will most likely find it to be an over the top exercise in exaggerated hyperventilation.” I do believe that we are at a crossroads, a unique and decisive moment, even what Balthasar called “Ernstfall, which is a German term that means a moment of existential crisis that imposes on us a choice.” It is because I do realize the urgency of the moment that what Chapp is saying does not speak to me. Chapp “pulls no punches.” He “cannot speak otherwise or in a different tone because these are most truly my deepest convictions.” What is the choice this existential crisis demands of us? Nothing less than “a repristination of the faith.” And when do we want it? “Now!”

A person who offers repristination of the faith as the remedy to the existential crisis that the world is suffering today is someone with no clue as to the real depth of what we are facing and the stark choices the times are demanding we make. This is evident, too, in Chapp’s disparagement of the resisters amongst us, “burning hundreds of draft cards in protest of the Vietnam War seemed of far more importance than growing beets for the local community food pantry.” How to respond to such ignorance? Dr. Martin Luther King said of those who questioned his own participation in protests against that war, “Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.”

In the December, 1966, issue of The Catholic Worker, Thomas Merton in an article “Albert Camus and the Church,” quoted Camus, “What the world expects of Christians is that Christians should speak out, loud and clear, and that they should voice their condemnation in such a way that never a doubt, never the slightest doubt, could rise in the heart of the simplest man. That they should get away from abstraction and confront the blood-stained face history has taken on today. The gathering we need today is the gathering together of men who are resolved to speak out dearly and pay with their own person.” Chapp’s deepest conviction, on the contrary, is what the world needs of Christians today is a retreat into the abstraction of repristination.

“If you listen to Peter and Dorothy carefully, you will understand that for them” Chapp says, “the most subversive ‘political’ action that one can engage in is going to Mass.” But Chapp does not listen to Peter and Dorothy. Even here, he must resort to quoting Joseph Ratzinger (again) in order to explain what Peter and Dorothy thought. Peter and Dorothy appear in Chapp’s Confession only as bobble-head dolls on his dashboard, thoughtlessly nodding at every bump in the road. Listening to Ratzinger has not helped Chapp understand Peter and Dorothy.

Listening to Peter carefully, you will understand that for him

“We cannot imitate the Sacrifice of Christ on Calvary by trying to get all we can.

We can only imitate the Sacrifice of Christ on Calvary by trying to give all we can.”

Listening to Dorothy carefully, you will understand that that for her

“The great scandal of the age is that those without the sacraments are so often superior in charity, courage, even laying down their lives for their brothers, to the ‘practicing Catholic’ who partakes of the Sacraments of Penance and Holy Eucharist and then stands by while his brother is exploited, starved, beaten, and goes on living his bourgeois life, his whole work being to maintain ‘his standard of living,’ and neglecting the one thing needful, love of God and brother. In the union field, even in this country, it has been the union organizer, often the Communist, who has risked jail and beatings to organize textile workers and migrant workers while the Catholic too often stands by and accepts the benefits of the union and does not earn them. Both Mauriac and Maritain have said that he who loves his brother and works for justice is working for Christ even though he deny Him; that is, deny Him as he sees Him in the nominal Christian. Perhaps they accept Him on the Cross where He took our sins upon Himself. What a grace to recognize Him so!”

Dorothy Day’s conviction of helping the poor and struggling is inspiring. How can I help?

John, look up info to see whether any Catholic Worker communities exist near you, or whether a particular community resonates with your abilities to help. The website http://www.catholicworker.org may be helpful!

Hi, John. I’m not living in a CW house, but I’ve had a long and grateful association with many of the houses in a network of many such places in the U.S. and abroad. Here is a link to a website listing all of the communities:

https://catholicworker.org/a-list-of-all-catholic-worker-communities/

You could subscribe to the CW paper published by the NY CW community by paying the 12 cent subscription rate. More is always welcome.

Please let me know if you have specific interests. Kathy.vcnv@gmail.com

boar President, World BEYOND War