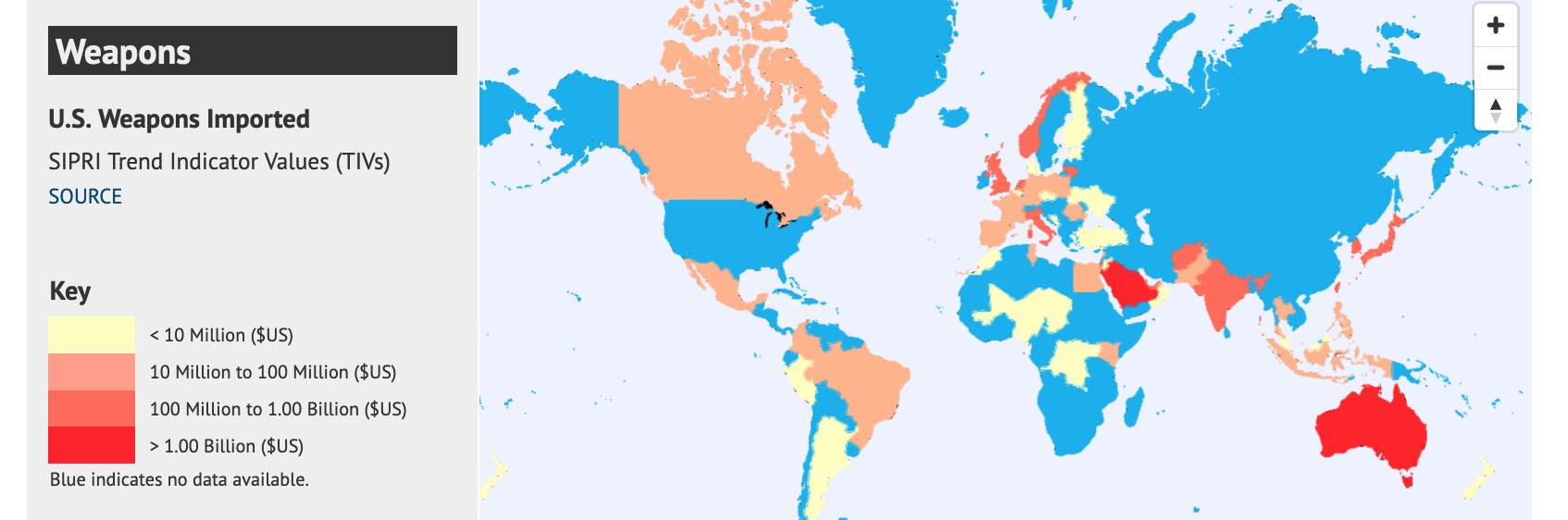

Image from Mapping Militarism.

By David Swanson, World BEYOND War, November 2, 2021

U.S. presidential election campaigns have been known to focus on the slogan “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Efforts to explain the behavior of the U.S. government ought to put a little more focus on a different slogan, found in the headline above.

Andrew Cockburn’s fantastic new book, The Spoils of War: Power, Profit, and the American War Machine, builds a case that U.S. foreign policy is driven primarily by weapons profits, secondarily by bureaucratic inertia, and little if at all by any other interests, be they defensive or humanitarian, sadistic or insane. In the tales that corporate media spins, of course, humanitarian interests loom large and the whole enterprise is labeled “defense,” whereas in the view I’ve held for decades and still do, you can’t explain it all with profits and bureaucracy — you have to throw in viciousness and lust for power. (Even Cockburn seems to see the notorious preference for F35s over A10s as not only for profit but also for the sake of killing more innocent people and knowing less about them. Even Cockburn quotes General LeMay promising to attack Russia of his own initiative with no profit interest at play.) But the primacy of profit in the war machine should not be open to debate. At least, I’d like to see someone read this book and then dispute it.

Much of Cockburn’s book was written pre-Trump, which is to say before the U.S. President held press conferences to say the quiet parts aloud and announce publicly, among other things, that it’s the weapons sales, stupid. But Cockburn’s reporting makes clear that Trump changed primarily how things were talked about, not how they were done. Coming to grips with this can help us understand additional aspects of governance beyond the book, such as why militaries are given a waiver in climate agreements, or why nuclear weapons interests drive support for nuclear energy — in other words, seemingly nonsensical policies in various areas can be found to make sense when one stops thinking of the U.S. government as something different from a weapons dealer.

Even nonsensical, endless, disastrous, and unsuccessful wars are often explained as sensible glowing successes if understood, not in terms of the propaganda used for them, but as weapons marketing schemes. Of course this won’t work as well for any other government, as only the U.S. government dominates global weapons sales, and only a handful of governments play a major role in the field at all, while U.S. government weapons purchases (of U.S. weapons) equal roughly what the entire rest of the world spends on weapons.

The evidence compiled by Cockburn suggests a longstanding pattern of increased military spending actually producing less effective militarism on its own terms. We’re all used to watching Congress buy non-functioning weapons that the Pentagon doesn’t even want but which are built in the right states and districts. But other factors apparently compound the trend. The more complex the weapon, the greater the profits — this factor alone often results in a smaller number of fancier weapons. In addition, in many cases, the more faulty the weapons, the greater the profits, as companies are simply paid extra to fix things rather than being held to account. And the loftier the claims for weapons, even when unproven, the greater the profits. The claims need not be believed, so long as they can be marketed abroad as threats. And even there, no expectation of being believed is required. This is both because even pretended belief in a weapon can lead to war, and because the military industries in other countries are looking for excuses to justify their own weapons, completely regardless of whether the weapons they are countering are capable of hurting a fly. Cockburn even recounts a suspiciously timed incident of a Soviet sub appearing near San Francisco just when a Conrgessional vote on U.S. weapons was in peril.

Peace-oriented organizations (and Bernie Sanders) for many years have highlighted faulty weapons, waste, fraud, and corruption as arguments for reducing military spending. War abolition organizations have argued that the weapons that don’t work are the least bad weapons, that their not working is a silver lining, that the diversion of resources into them is a deadly tradeoff when humanitarian and ecological needs go unfunded, but that the first weapons to oppose are the ones that actually kill the most efficiently. A question that has not been sufficiently answered is whether we can united and enlarge our numbers through recognition of weapons profits as the main source of militaries and wars, rather than a flaw in a respectable system. Can we actually learn and act on the comment of Arundhati Roy that weapons used to be made for wars, whereas wars are now made for weapons?

U.S. claims for “missile defense” are false and wildly exaggerated, as Cockburn documents. So, apparently are Vladimir Putin’s claims to counter that fictional technology with hypersonic missiles. So, indeed, seem to be U.S. claims to be plausibly pursuing similar hypersonic weapons — as they have been doing off-and-on since they brought over a Nazi slave-driver named Walter Dornberger to work for the U.S. military. Does Putin believe U.S. missile defense claims, or want to fund weapons-dealing cronies, or act on his own macho lust for power? The U.S. weapons dealers now cashing in on their own hopeless hypersonic missiles probably don’t care.

The Saudi war on Yemen is largely driven by U.S. weapons sales to Saudi Arabia. So is the coverup of the Saudi government role in 9/11. Cockburn covers both of these topics extensively. Saudi Arabia even pays the U.S. $30 million a year to host a U.S. weapons sales team that sells them more weapons.

Afghanistan too. In Cockburn’s words: “The record shows America’s Afghan war was nothing other than a prolonged and entirely successful operation — to loot the U.S. taxpayer. At least a quarter of a million Afghans, not to mention 3,500 U.S. and allied troops, paid a heavier price.”

Not just weapons and wars are driven by profits. Even the expansion of NATO that kept the Cold War alive was driven by weapons interests, by the desire of U.S. weapons companies to turn Eastern European nations into customers, according to Cockburn’s reporting, together with the interest of the Clinton White House in winning the Polish-American vote by bringing Poland into NATO. It’s not just a drive to dominate the global map — although it’s certainly a willingness to do so even if it kills us.

The collapse of the Soviet Union is explained in Cockburn’s reporting as self-inflicted corruption by its military industrial complex, more a hopeless jobs program than competition with the United States. If a purportedly communist state can succumb to the mirage of military jobs (we know that military spending actually harms an economy and removes rather than adds jobs) is there much hope for the United States where capitalism is a faith and people actually believe the militarism protects their “way of life”?

I do wish Cockburn hadn’t claimed on page xi that Russia took over Ukraine and on page 206 that a ridiculously tiny number of people died in the war on Iraq. And I hope he didn’t leave Israel out of the book because his wife wants to run for Congress again.