By David Swanson, World BEYOND War, September 9, 2021

U.S. high schools should teach courses on Guantanamo: what not to do in the world, how not to make it even worse, and how not to compound that catastrophe beyond all shame and recovery.

As we tear down Confederate statues and continue brutalizing victims in Guantanamo, I wonder if in 2181, had Hollywood still been around, it would have made movies from the perspective of Guantanamo’s prisoners while the U.S. government commited new and different atrocities to be bravely confronted in 2341.

That is to say, when will people learn that the problem is cruetly, not the particular flavor of cruelty?

The purpose of the Guantanamo prisons was and is cruelty and sadism. Names like Geoffrey Miller and Michael Bumgarner should become permanent synonyms for the twisted dehumanizing of victims in cages. The war is supposedly over, making it difficult for aging men who were innocent boys to “return” to the “battlefield” if freed from the Hell on Earth stolen from Cuba, but nothing ever made sense. We’re on President #3 since promises were first made to shut Guantanamo down, yet it moans and rattles on, brutalizing its victims and their captors.

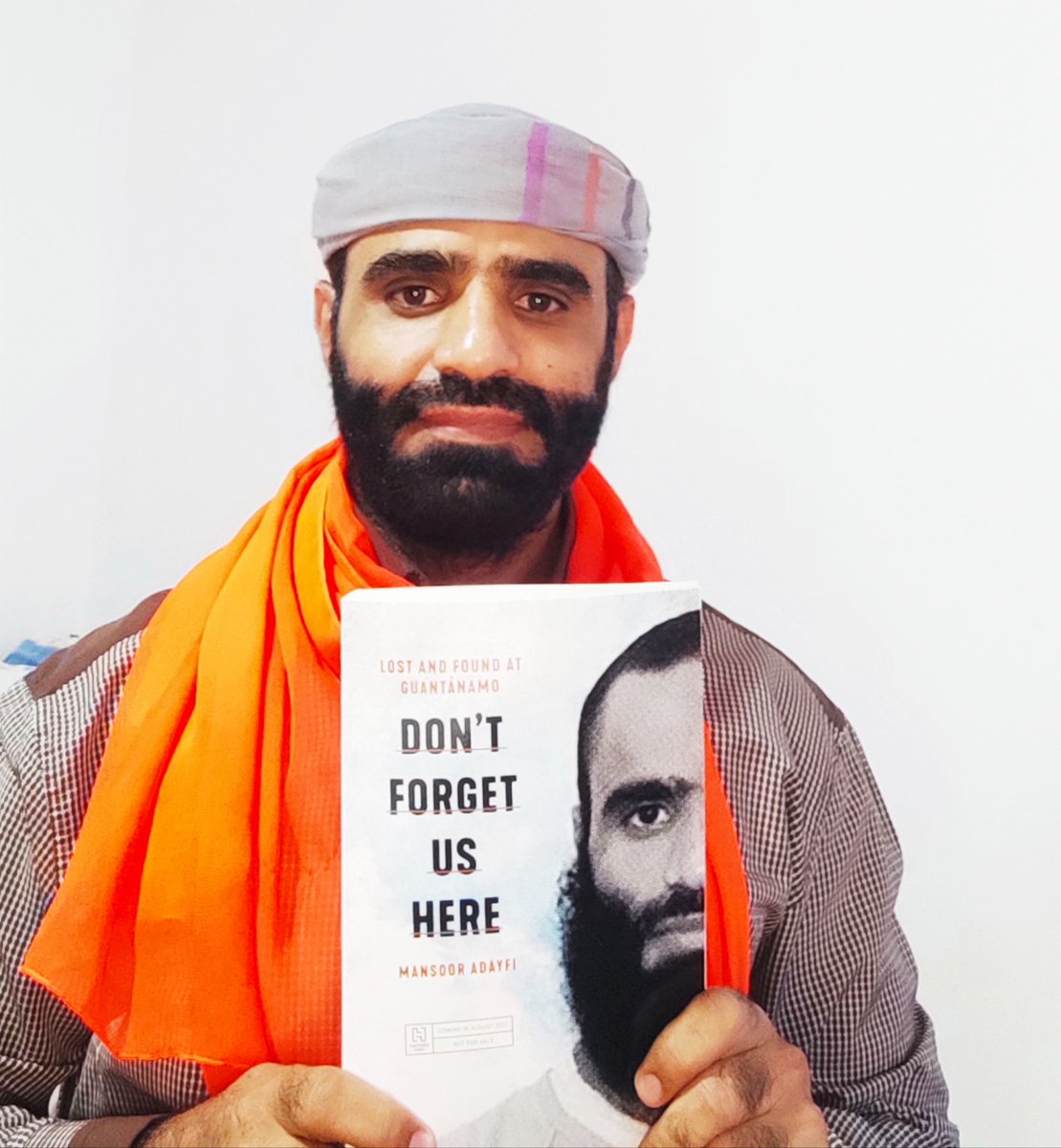

“Don’t Forget Us Here” is the title of Mansoor Adayfi’s book about his life from age 19 to age 33, which he spent in Guantanamo. He could not be seen as the youngster he was when first kidnapped and tortured, and was seen instead — or at least the pretense was made — that he was an important top anti-U.S. terrorist. That didn’t require seeing him as a human being, quite the opposite. Nor did it have to make any sense. There was never any evidence that Adayfi was the person he was accused of being. Some of his imprisoners told him they knew it was false. He was never charged with any crime. But at some point the U.S. government decided to pretend he was a different top terrorism commander, despite the lack of any evidence for that one either, or any explanation of how they could have captured such a person accidentally while imagining that he was someone else.

Adayfi’s account begins like so many others. He was abused by the CIA in Afghanistan first: hung from a ceiling in the dark, naked, beaten, electrocuted. Then he was stuck into a cage in Guantanamo, having no idea what part of the Earth he was in or why. He only knew the guards behaved like lunatics, freaking out and screaming in a language he couldn’t speak. The other prisoners spoke a variety of languages and had no reason to trust each other. The better guards were awful, and the Red Cross was worse. There seemed to be no rights, except for the iguanas.

At any opportunity, guards stormed in and beat prisoners, or dragged them off for torture/interrogation or solitary confinement. They deprived them of food, water, healthcare, or shelter from the sun. They stripped them and “cavity-searched” them. They mocked them and their religion.

But Adayfi’s account develops into one of fighting back, of organizing and rallying the prisoners into all variety of resistance, violent and otherwise. Some hint of this appears early on in his atypical reaction to the usual threat to bring his mother there and rape her. Adayfi laughed at that threat, confident that his mother could whip the guards into shape.

One of the main tools available and used was the hunger strike. Adayfi was force-fed for years. Other tactics included refusing to come out of a cage, refusing to answer endless ridiculous questions, destroying everything in a cage, inventing outrageous confessions of terrorist activity for days of interrogations and then pointing out that it was all made-up nonsense, making noise, and splashing guards with water, urine, or feces.

The people running the place chose to treat the prisoners as subhuman beasts, and did a pretty good job of making the prisoners play the part. The guards and interrogators would believe almost anything: that the prisoners had secret weapons or a radio network or had each been a top ally of Osama bin Laden — anything other than that they were innocent. The relentless interrogation — the slaps, the kicks, the broken ribs and teeth, the freezing, the stress positions, the noise machines, the lights — would go on until you admitted being whoever they said you were, but then you’d be in for it bad if you didn’t know lots of details about this unknown person.

We know that some of the guards really thought all the prisoners were crazed murderers, because sometimes they’d play a trick on a new guard who fell asleep and put a prisoner near him when he awoke. The result was sheer panic. But we also know it was a choice to view a 19-year-old as a top general. It was a choice to suppose that after years and years of “Where is Bin Laden?” any answer that actually existed would still be relevant. It was a choice to use violence. We know it was a choice to use violence because of an extensive multi-year experiment in three acts.

In Act I, the prison treated its victims as monsters, torturing, strip-searching, routinely beating, depriving of food, etc., even while trying to bribe prisoners to spy on each other. And the result was often-violent resistance. One means that sometimes worked for Adayfi to lessen some injury was to beg for it like Brer Rabbit. Only by professing his deep desire to be kept near screaming loud vacuum cleaners put there, not to clean, but to make so much noise around the clock that one couldn’t talk or think, did he get a break away from them.

The prisoners organized and plotted. They raised hell until interrogators stopped torturing one of their number. They jointly lured General Miller into position before hitting him in the face with shit and urine. They smashed their cages, ripped out the toilets, and showed how they could escape throught the hole in the floor. They went on mass hunger srike. They gave the U.S. military vastly more work — but then, is that something the military didn’t want?

Adayfi went six years without communication with his family. He became such an enemy of his torturers that he wrote a statement praising the crimes of 9/11 and promising to fight the U.S. if he got out.

In Act 2, after Barack Obama became president promising to close Guantanamo but didn’t close it, Adayfi was permitted a lawyer. The lawyer treated him as a human being — but only after being horrified to meet him and not believing he was meeting the right person; Adayfi did not match his description as the very worst of the worst.

And the prison changed. It became basically a standard prison, which was such a step up that prisoners cried for joy. They were allowed into common spaces to sit and talk to each other. They were allowed books and televisions and carboard scraps for art projects. They were allowed to study, and to go outside into a recreational area with the sky visible. And the result was that they didn’t have to fight and resist and get beaten all the time. The sadists among the guards had very little left to do. Adayfi learned English and business and art. Prisoners and guards struck up friendships.

In Act 3, in response to nothing, apparently due to a change in command, old rules and brutality were reintroduced, and the prisoners responded as before, back on hunger strike, and when intentionally provoked by damaging Qur’ans, back to violence. The guards destroyed all the art projects the prisoners had made. And the U.S. government offered to let Adayfi go if he would dishonestly testify in court against another prisoner. He refused.

When Mansoor Adayfi was finally freed, it was with no apology, except unofficially from a Colonel who admitted to knowing his innocence, and he was freed by forcing him to a place he did not know, Serbia, gagged, blindfolded, hooded, earmuffed, and shackled. Nothing had been learned, as the purpose of the whole enterprise had included from the start the avoidance of learning anything.