‘How to go forward with Catholic Worker anarchism as the movement nears its ninetieth anniversary and the very concept is denied, slandered and discredited from all sides?’

An article written by Catholic Worker and academic Lincoln Rice, Catholic Worker Anarchism at a Crossroads: The Difficulty of Addressing Anti-Blackness, published by the Political Theology Network under the aptly named category ‘CATHOLIC RE-VISIONS,’ is troubled with historical inaccuracies and unsupported assumptions, beginning with his premise, ‘As the Catholic Worker movement confronts anti-Black racism more earnestly, questions arise about whether taking an active anti-racism stance can be reconciled with Catholic Worker anarchism, specifically when dealing with the state.’

As the cause for Dorothy Day’s canonization as a saint progresses through the Vatican bureaucracy, there is much discussion about the meaning of the words ‘anarchism’ and ‘anarchist’ as applied to Dorothy and to the Catholic Worker movement that she founded with Peter Maurin in 1933. For many who want to see her sanctity formally recognized, including some Catholic bishops and theologians, the word ‘anarchism’ is a is a scandal to be denied or explained away.

Some, like Cardinal John O’Connor who launched her canonization process in 1997, ‘exonerate’ Dorothy by relegating her anarchism to her sinful, unconverted youth, repented of and forgiven. Another strategy employed for absolving Saint Dorothy from the stain of anarchy, is to claim that the anarchism that she espoused was so completely different from what other anarchists promote that the word does not really apply to her or the Catholic Worker, at all. ‘She preferred the words libertarian, decentralist, and personalist’ over anarchist, religion scholar June O’Connor is often quoted as saying, but it is not clear where that idea came from.

Dorothy Day, ‘I did not “talk Jesus” to the anarchists’

All her life, Dorothy celebrated her anarchism and stressed her solidarity with her anarchist comrades. ‘When it is said that we disturb people too much by the words pacifism and anarchism, I can only think that people need to be disturbed,’ Dorothy said in her April 1954 column. In 1974, after attending a conference of anarchists, Dorothy wrote, ‘I did not “talk Jesus” to the anarchists. There was no time to answer the one great disagreement which was in their minds–how can you reconcile your Faith in the monolithic, authoritarian Church which seems so far from Jesus who “had no place to lay his head,” and who said “sell what you have and give to the poor,”–with your anarchism? Because I have been behind bars in police stations, houses of detention, jails and prison farms, whatsoever they are called, eleven times, and have refused to pay Federal income taxes and have never voted, they accept me as an anarchist. And I in turn, can see Christ in them even though they deny Him, because they are giving themselves to working for a better social order for the wretched of the earth.’ A pacifist herself, Dorothy owned her kinship even with anarchists who promoted the often violent ‘propaganda of the deed,’ like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, whom in 1975 she described as ‘the two famous and lovable anarchists who were deported to Russia after the First World War.’

Lincoln Rice employs a third way to neutralize the historical anarchism of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker, by equating it with racial liberalism in a way that makes it appear ridiculous and odious to any person concerned with racial justice. His opening question, whether taking an active anti-racism stance can be reconciled with Catholic Worker anarchism, also begs the question whether taking an active anti-racism stance can be reconciled with Black Panther anarchism, except that he also presupposes that anti-racist activists in the affected communities are monolithic in their approach to the state. ‘Often in the news today, anarchism is widely misunderstood,’ writes Livia Gershon in her article The Real Story of Black Anarchists. ‘One myth is that it’s a movement for white people.’ Intentionally or not, Lincoln either does not accept the existence of Black anarchists, past and present, or he judges them and other activists of color who are suspicious of liberal politics as irrelevant. In a 1987 article in The Catholic Worker titled Racism Among Us – Spoken and Unspoken, Jane Sammon suggested ‘How instructive it would be to include the works of such thinkers as W. E. B. Du Bois, Franz Fanon, and Malcolm X in our Catholic Senior High Schools,’ thinkers who ‘expose the crime of racism and the cutting edge of the long and bitter struggle of the Black people throughout history.’ It would be instructive to include them in a discussion of Catholic Worker anarchism at a crossroads as well.

Lucy Parsons, ‘I am an anarchist!’

While Dorothy was inspired by the writings of European anarchists like Peter Kropotkin, her personal experience with anarchism and anarchists began as a young woman when she joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). While she resisted joining the Communist party, Dorothy did join this radical union and was loyal to it her whole life. In the IWW’s founding convention 1905, Lucy Parsons, a Black woman born into slavery, was the only woman to address the assembly. Already an activist for many years when she co-founded the IWW, her 1886 ‘I am an Anarchist’ speech is a classic of American radicalism.

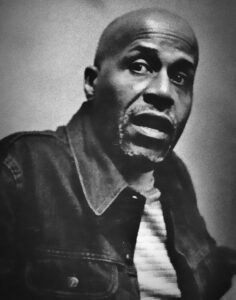

Martin Sostre, ‘face of anarchism at the Catholic Worker’ in the 1970s

My introduction to anarchism when I first came to the Catholic Worker in New York in the mid-1970s, was Martin Sostre. He was the face of anarchism at the Catholic Worker, meaning that his picture was on the wall and his name was published in the pages of The Catholic Worker newspaper 23 times from 1970 to 1979. Martin Sostre was a Black Puerto Rican activist who ran an anarchist bookstore in Buffalo, was targeted by the FBI’s COINTELPRO and falsely imprisoned from 1967 to 1976.

Lincoln says, ‘As the Catholic Worker moves forward, Day’s disparaging comments about Black political action bring Catholic Worker anarchism to a crossroads.’ This is one of several provocative allegations made in his short article attributing bad faith or ignorance to Dorothy and the Catholic Worker without providing a citation.

For any white activist to make disparaging remarks about Black political activism, Dorothy Day included, would be discrediting. Such a comment, however inexcusable, would have been exceptional, though, and out of character for Dorothy and not reflective of Catholic Worker anarchism. I am skeptical that she ever made such remarks, but even if she did slip, the overall record of her work shows that ‘respectful differences with esteemed comrades’ is the more accurate description of Dorothy’s and the Catholic Worker’s relationship to Black political action. In 1956, for example, Dorothy wrote in her regular column, ‘even though the editors of The Catholic Worker do not believe in the vote, in elections as conducted today, we do agree that man [sic] wants a part to play, a voice to speak in his community, and this is usually exemplified by the vote.’

‘Despite her espousal of anarchism,’ Lincoln says, ‘Day provided qualified support for Castro’s Cuba.’ He characterizes Dorothy’s support for the Cuban revolution, though, as the rare exception inconsistent with her anarchism, rather than her typical and often stated support for people’s struggles for liberation. Dorothy likewise expressed admiration for the revolutionary Ho Chi Minh before and during the U.S. war of aggression in Vietnam. Dorothy’s praise for the policies Julius Nyerere, the socialist Catholic president of Tanzania, was particularly effusive. ‘To me (Nyerere’s) Arusha Declaration sounds like Peter Maurin’s ideas incarnate,’ she said.

Julius Nyerere, ‘sounds like Peter Maurin’s ideas incarnate…’

Dorothy’s regard for peoples’ struggles in the U.S. was just as generous and broad. Dorothy was unwaveringly Catholic, pacifist and anarchist, but she was always able to respect, support, march with and learn from people who were not Catholic, not pacifist and not anarchist. She did not use herself, her faith or her ideology, as the yardstick with which she judged others. ‘I have been reading about Kenneth Kaunda, president of Zambia,’ she wrote in 1970. ‘He and Julius Nyerere in Africa, stand in my mind with Cesar Chavez, Danilo Dolci, Vinoba Bhave, Dom Helder Camara, Mrs. Martin Luther King, Ralph Abernathy, and others who have the vision and the integrity which enlightens our minds and brings us bright hope for the future. God is with them. May He bless and protect them.’ In this list of activists revered by Dorothy, none was an avowed anarchist, two were elected heads of African states.

‘Regarding their interactions with local, state, and federal governments,’ Lincoln says, ‘Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement have largely adopted a stance of nonparticipation with few exceptions.’ Lincoln represents Catholic Worker anarchism as something far more rigid, dogmatic and doctrinaire than it is. As in other matters, there is ‘no party line’ in the Catholic Worker regarding anarchism, but Lincoln’s take on it is singular. In 1992, neighbors in our little farm town, Maloy, Iowa, asked me to run for mayor and elected me (with all 12 votes cast!). Aside from some gentle ribbing from friends, no one in the movement criticized me for holding elected office. I even got a shout out from Ric Rhetor in The Catholic Worker newspaper: ‘Brian, now living at Strangers and Guests CW in Maloy, lowa, with his wife Betsy Keenan and children Elijah and Clara, was here in New York at the CW in the 70s. There are 35 citizens of Maloy, and the activist Mr. Terrell is now Mayor! Small is beautiful—it reminds us of how Dorothy Day used to say she could see herself getting involved in local politics if she had stayed in one place long enough —being the indefatigable pilgrim that she was.’

Anarchism in the Catholic Worker tradition is not about ideological purity at the expense of real human needs, nor is it passive nonparticipation in the way Lincoln suggests. ‘At the very hour we go to press there is still doubt as to the outcome of the Burke-Wadsworth Conscription Bill before Congress,’ Dorothy wrote in the September 1941 issue concerning the pending military draft. ‘If the unorganized opposition can keep on protesting and deluge their Congressmen with letters of opposition, there is still a chance to defeat the bill. It is not too late to make your protest’ (bold face in the original).

Some personal examples of engaging the state as an anarchist: During the Iraq sanctions in the 1990s and after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Catholic Workers were at the core of protest campaigns aimed at challenging members of congress to break from these policies. I have never voted in a U.S. senate election, but I have been arrested more times that I can remember in the offices of Iowa’s senators. In the 2008 Iowa caucus starting the presidential election process, I canvased each of the broad field of candidates on their position toward the various wars at the time- every one of them was pro-war, of course, and so we organized protests and sit-ins at the various campaign headquarters. I did not go to the caucus because that night I was in jail for trespassing at Obama’s campaign office. Some of our political action friends angrily objected to our activities, insisting that rallying behind whichever Democratic candidate might win an election regardless of how vile and regressive their policies, was the only responsible course to take. From our side, the disagreements were respectful. It has been my experience that it is liberal politics that tends to limit activists’ creativity and not Catholic Worker’s traditional anarchism, as Lincoln believes.

To be a ‘gadfly’ in the face of the oppressive systems, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr wrote from the Birmingham Jail, or to ‘Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence,’ as Henry David Thoreau counseled, and not passivity, is what Catholic Worker anarchism is about. To simply counsel Black families that come into contact with child protective services to not cooperate with the state, as Lincoln suggests Catholic Workers might do, would be a grotesque and irresponsible distortion of our traditional anarchism.

Another position that Lincoln attributes to Dorothy without backing it up is ‘Day wanted to believe that African Americans in the United States could improve their lives without any political involvement.’ This is certainly not true. There are many kinds of ‘political involvement’ and voting is only one of them. Even many those who strongly advocate for the vote recognize that the vote is worthless without other political involvement. Everyone, Dorothy said, wants ‘a part to play, a voice to speak in his community, and this is usually exemplified by the vote,’ but as Malcolm X warned and many Black activists today believe, electoral politics and the horse trading and compromise that it necessarily entails can be a drain on real political progress.

Lincoln says ‘I believe the primary reason for the tepid response of the Catholic Worker movement to anti-Black racism has its origin in racial liberalism—a mindset that does not tolerate “overt bigotry,” but leaves institutional or structural forms of racism largely unaddressed. This viewpoint underestimates the compounded wealth and privileges that white people have accumulated through centuries of Black slavery and anti-Black discrimination, believing that the elimination of overt discrimination alone is an adequate response to racism without any need for restorative policies.’ Lincoln provides no foundation for this belief.

As an autonomous collection of persons and communities, the Catholic Worker movement is more diverse than The Catholic Worker newspaper published by the New York community, but if such a mindset were prevalent, it would be articulated in its pages. The Catholic News Archive catalogues all the issues of The Catholic Worker from 1940 to 2019- a search of the word ‘racism’ in their data base yields 294 hits. In the newspaper and other primary sources, a mindset of racial liberalism that ignores structural racism is not immediately evident, but what appears to be a ‘serious and critical appraisal of how racism infects every aspect of U.S. culture’ is ubiquitous. I offer a few examples almost at random:

Front page of the July, 1970, issue of the paper featured an article by Gerald C Montesano, Black Panther Party: In Quest Of Justice, opens ‘Those of us born white and middle class, have had to learn a new understanding of violence. The Vietnam war, the Black and Third World liberation struggles have given us a new focus,’ and continues with a quote from Thomas Merton, ‘The population of the affluent world is nourished on a steady diet of brutal mythology and hallucination, kept at a constant pitch of high tension by a life that is intrinsically violent in that it forces a large part of the population to submit to an existence which is humanly intolerable… The problem of violence, then, is not the problem of a few rioters and rebels, but the problem of a whole social structure which is outwardly ordered and respectable, and inwardly ridden by psychopathic obsessions and delusions.’

In the previously mentioned 1987 article in The Catholic Worker, Racism Among Us – Spoken and Unspoken, Jane Sammon insisted that ‘To live in Christ Jesus, we must account for our own sins of racism. We must admit, in the words of Martin King, spoken nearly twenty years ago, that “racism is a way of life for a vast majority of white Americans, spoken and unspoken, acknowledged and denied, subtle and sometimes not so subtle – the disease of racism permeates and poisons a whole body politic. And I can see nothing more urgent than for America to work passionately and unrelentingly – to get rid of the disease of racism.”’

In December, 1961, The Catholic Worker published ‘The Race Problem and the Christian Conscience’ by Philip Berrigan. Still active in the priesthood at the time, Phil painfully indicts the Catholic Church’s institutional racism and recognizes that ‘the greatest factor in the painfully slow progress of Race Relations in this country is not the racists common to both North and South, but the silence of the “Moderates,” the fact that many good people sit on their hands in a position of safety, watching the life stream pass them by, apprehensive, uncommitted, merely “good.”’ It is worth a look at a scan of that entire issue to see the space that the editors gave Phil’s ‘tepid response’ to systematic racism in their Christmas issue. At more than 8900 words, it starts on page one, fills pages four, five and six completely, finishing on pages seven and eight of a tabloid sized paper. If not the longest, it has to be in the running for the longest article that The Catholic Worker has ever run.

Thirty-five years later, but still too early to be counted as a serious or critical appraisal, Phil wrote, (Fighting the Lamb’s War: Skirmishes with the American Empire 1996) ‘We (the United States of America) had never really chopped down the slavery tree; we just pretended, now and again, to trim its limbs. The roots grew into our own backyards, wound through our homes, undermined our schools, strangled our sense of reason and fair play. I discovered that the roots of this poisonous tree are inextricable from our economic system. Greed waters these roots, keeps them healthy, enables them to keep expanding their power and influence. Avarice transplants the tree when it isn’t flourishing. Exploitation supplies the tree with nutrients and fertilizer.’ Phil was and he remains one of the most influential leaders in the Catholic Worker movement. In response to Phil’s writings from prison, Stokely Carmichael, Kwame Ture, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the ‘Honorary Prime Minister’ of the Black Panther Party said ‘Philip Berrigan is the only white man who knows where it’s at.’ Lincoln Rice disagrees with Kwame Ture’s assessment of Phil. It is as if the place where a white person can gain a serious and critical appraisal of racism is not the prison but the university.

Lincoln cites ‘the obvious racial divisions in urban houses of hospitality where the staff of almost completely white and the guests are almost completely people of color,’ as if it were a problem never observed or addressed in the past. In 1971, Jan Adams wrote about this, ‘Nor are those at the Worker, who consciously try to overcome hatred, free from the taint of American racism. Much as we try to extend our sense of the human family to every individual who comes to us, our perceptions are colored by living in a racist society. For example, I have caught myself responding less sympathetically to the black alcoholic demanding a clean shirt at a moment when I have five other matters to attend to, than I would to a white man with the same Inconvenient request. …. Interactions between the races at the Worker thus partake fully in the current American agony. Despite great tensions, we stumble along, doing the best we can—hoping to maximize the truthful, loving interaction between unique, often agonized, individuals of both races.’ While Lincoln believes that it has gone unnoticed until very recently, most urban Catholic Workers over the years have felt keenly the tension that Jan articulated.

No one I know in the movement, and I venture that no one ever in the pages of The Catholic Worker, suggests that there is no need for restorative policies in response to racism, but Lincoln provides two examples that he thinks suffice to prove that this is a commonly held belief. ‘First,’ he says, ‘Dorothy Day promoted a colorblind mentality for teaching children about racism, which actually increases the likelihood that a white child will become ingrained with racial prejudices.’ Lincoln provides no context, how, when, where or to whom Dorothy promoted a colorblind mentality for teaching children. If she said something like this, it was a stupid thing to say but is not definitive of her approach to racism and should be balanced, at least, with Dorothy’s celebration in 1971 that ‘“Black studies” into our own situation in the United States, our history, culture and religion is going on apace.’ Jane Sammon’s previously quoted call for a curriculum to ‘expose the crime of racism and the cutting edge of the long and bitter struggle of the Black people throughout history’ is more representative of views within the movement, past and present, than what Lincoln alleges that Dorothy promoted about colorblind education.

Lincoln’s second example is dubious, as well: ‘Day stated in the 1960s that more would have been accomplished for racial justice if civil rights activists focused less on political rights and more on creating financial and societal infrastructure for African Americans. This argument ignores history, which is replete with examples of successful Black entrepreneurs being intimidated, lynched, or having their businesses destroyed. The worst instance of this was the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, which resulted in whites burning down thirty-five square blocks in the successful Black area of the city and killing approximately 300 African Americans. Black financial and societal infrastructure provided scant shelter from white supremacy in the United States.’

I grant that she said probably something like this once in that decade, but the context would be helpful. In any case, even as Lincoln presents it, his argument equally shows the limits of civil rights activists seeking political rights. History is also replete with potential Black voters and successful Black politicians being intimidated, lynched, or having their elected governments overturned, beginning with the reconstruction era riots. Even constitutionally guaranteed voting rights and the protection of the Union Army provided scant shelter from white supremacy in the United States. That good ideas in history have been met with violent responses does not invalidate them.

The accomplishments of Black business leaders of Tulsa in the early 1900s were heroic and the destruction and murder that followed in the riots of 1921 was horrendous. Connecting Dorothy to them, however, as if the creation of a ‘Black Wall Street’ was what she meant by ‘creating financial and societal infrastructure for African Americans’ dishonors the memories of those who were murdered there. The Black entrepreneurs of Tulsa were not revolutionists like Dorothy, nor anarcho-syndicalists trying to ‘build a new society in the shell of the old,’ like the IWW. They were people of business trying to make a living in the capitalist economy as it was, as they should have been allowed to do in peace. The Tulsa riots happened 12 years before the founding of the Catholic Worker. Even in her youth, Dorothy would never have counseled anyone, white or Black, to emulate Wall Street. The suggestion that the economic solutions she proposed ignore history and contributed to the killing of hundreds of African Americans is absurd.

The distinction between formal and material cooperation with evil that Lincoln wants Catholic Workers to learn from was taught in seminaries for a century and a half before Fr. Paul Hanly Furfey wrote The Fire on Earth. It is used to justify the practice of opting for ‘lesser evils’ that has proven helpful to fascist regimes worldwide and that has dominated liberal politics in the U.S. since the 1960s. It is not Fr. Furfey’s fault that the concept of material cooperation with evil has helped establish the Democratic Party’s ‘historical role as the graveyard of progressive movements.’ Lincoln believes that the Catholic Worker ‘would greatly benefit from a reexamination of its anarchism in light of the insights provided by the concept of material cooperation.’ Perhaps it is better said that moral theologians would greatly benefit from a reexamination of their concept of material cooperation in light of the insights provided by ninety years of living Catholic Worker anarchism experience?

Catholic Workers finding ways to constructively and nonviolently interact with evil (the state) without getting sucked into its political machinations is not new. Many of us work on this every day. Nor has a ‘more serious and critical appraisal of how racism infects every aspect of U.S. culture’ in the Catholic Worker ‘been absent until very recently.’ Of course, the ways that the Catholic Worker has dealt with racism in the past have been insufficient, but the same can be admitted, I hope, in reference to present efforts. If later generations of Catholic Workers judge the present as Lincoln judges the past, they will view today’s responses to anti-Black racism, Lincoln’s article included, as tepid indeed.

One cannot deny the progress made in recent years in the Catholic Worker confronting racism. The progress that is being made, however, is a continuum with the past, not the bright new beginning or the recently begun phenomenon some insist that it is. If today we can speak more articulately about racism, it is only because of those before who spoke up without the luxury of predecessors that we have today. Disparaging the intentions and actions of those who came before is only evading accountability for ourselves.

The challenge to Catholic Worker anarchism today, as in the past, is to discern how to live inside and yet resist what Dorothy called ‘this rotten, decadent, putrid industrial capitalist system.’ There is no universal template. Our tradition is a great resource, if we do not repudiate it. We need also to listen to our neighbors and those in communities most affected by systemic violence, recognizing always that in every community there are tensions regarding cooperation with the state and disagreements about how and when to engage or resist the political powers.

How to go forward with Catholic Worker anarchism as the movement nears its ninetieth anniversary and the very concept is denied, slandered and discredited from all sides? Rather than a reexamination of our anarchism in light of the insights provided by an abstract academic concept as Lincoln Rice suggests, I offer instead that we recall what Jan Adams wrote in The Catholic Worker in 1971, ‘Since we are forced to deal with American reality, we find no easy answers. Even when we see ourselves as a family, which though it quarrels accepts its relatedness, we risk defining our situation too facilely…. We are going to have to learn to love one another for our differences. And we are going to have to learn to love one another better in every way, so that the greed and power-hunger which reinforce our racism are beaten down.’

Brian Terrell is a college dropout and former mayor of Maloy, Iowa