By David Swanson, World BEYOND War, May 18, 2022

I often publish a review of a recent book and append a list of recent books advocating war abolition. I’ve stuck one book from the 1990s on that list, which is otherwise all 21st century. The reason I haven’t included books from the 1920s and 1930s is the size job it would be.

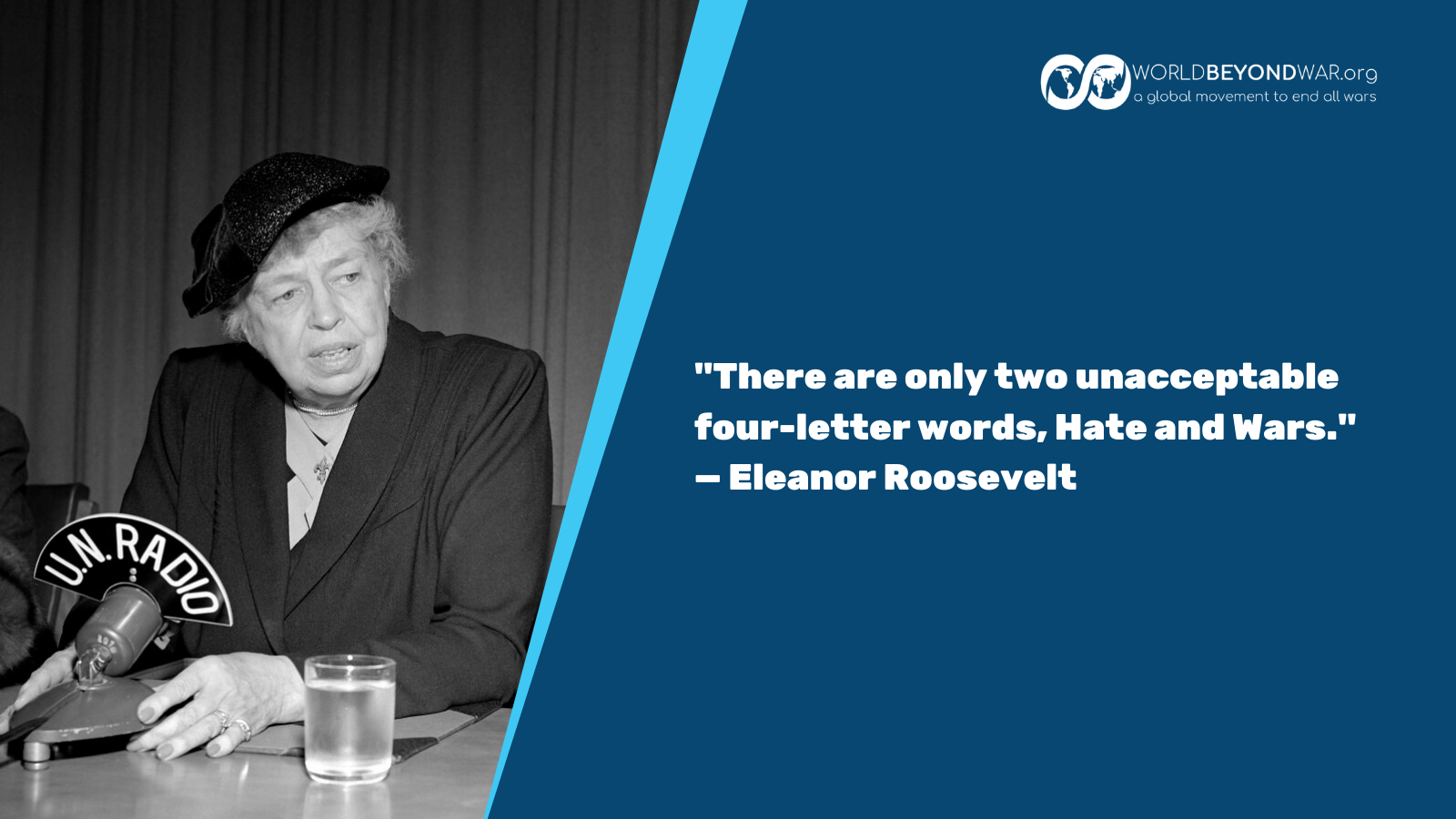

One of the books that would go on that list is 1935’s Why Wars Must Cease by Carrie Chapman Catt, Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt (I guess making clear she was married to the President outweighed mentioning her own name), Jane Addams, and seven other leading women activists for various causes.

Unbeknownst to the innocent reader, Catt had argued just as eloquently for peace prior to WWI and then supported WWI, whereas Eleanor Roosevelt had done little to oppose WWI. None of the 10 authors, with the possible exception of Florence Allen, despite urging steps in this book to prevent WWII, despite predicting it and arguing against it with great accuracy and urgency in 1935, would oppose it when it came. One of them, Emily Newell Blair, would go to work on propaganda for the War Department during WWII after making a powerful case in this book against the false belief that any war could be defensive or justified.

So, how do we take such writers seriously? This is exactly how mountains of wisdom that came out of the most peaceful years of U.S. culture have been buried. This is one reason we need to learn to leave WWII behind. The main answer is that we take these arguments seriously, not by placing the people who made them on pedestals but by reading the books and considering them on their merits.

Peace advocates of the 1930s are often caricatured as naive do-gooders with no awareness of the cruel real world, people who imagined that the Kellogg-Briand Pact would magically end all war. Yet these people, who had put in endless hours to create the Kellogg-Briand Pact never imagined for a second that they were done. They argued in this book for a need to halt the arms race and dismantle the War System. They believed that only abolition of militarism would actually prevent wars.

These are also the people who in the lead-up to and right through WWII pressured the U.S. and British governments, without success, to accept huge numbers of Jewish refugees rather than allow them to be slaughtered. The cause that some of these activists struggled for during the war actually became, some years after the war had ended, the cause that postwar propaganda pretended the war had been about.

These are also the people who marched and demonstrated for years against the arms race with and gradual buildup to war with Japan, something every good U.S. student will tell you never happened, since the poor wittle innocent United States was surprised by an attack out of a clear blue sky. So, I take the writings of 1930s peace activists quite seriously. They made war profiteering shameful and peace popular. WWII ended all of that, but what didn’t it end?

In this book we read about the new horrors of WWI: submarines, tanks, planes, and poisons. We see the understanding that talking about past wars and this latest war as examples of the same species was misleading. We can now, of course, look at the new horrors of WWII and hundreds of wars that have followed it: nukes, missiles, drones, and the overwhelming impact now on civilians and the natural environment, and question whether the two world wars are two examples of the same thing at all, whether either should be considered in the same category as war today, and whether the habit of thinking about war in pre-WWI terms endures out of ignorance or willful delusion.

These authors make a case against the institution of war for what it does to create hatred and propaganda, for its impact on morality. They lay out a case that wars breed more wars, including the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 breeding the disastrous Treaty of Versailles after WWI. They also make a case that WWI led to the Great Depression — a surprising idea to most U.S. students, every single one of whom will tell you that WWII ended the Great Depression.

For her part, Eleanor Roosevelt, in this book, makes a case that war should be ended as belief in witches and in the use of dueling had been ended. Can you just imagine the messy and immediate divorce that would follow the partner of any U.S. politician making such a statement today? Ultimately, this is the first reason to read writings from a different era: to learn what it was shockingly permissible to say.