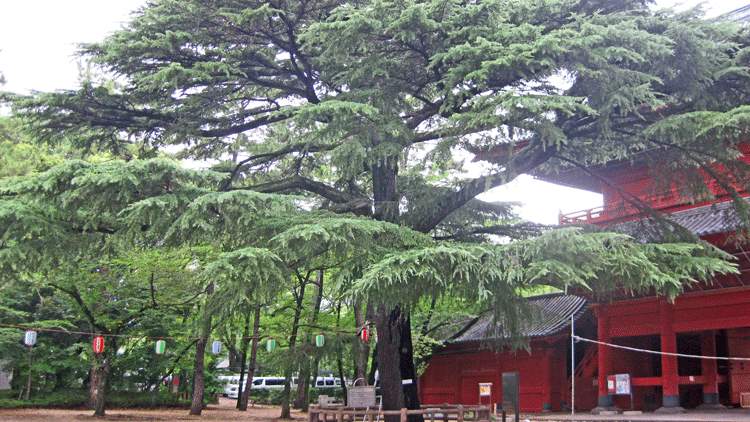

Grant Pine at Zojoji Temple, planted by then-U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant at the Tokugawa family shrine.

By David Swanson, World BEYOND War, October 25, 2021

Japan’s Prince Iyesato Tokugawa ought perhaps to be of more interest to us right now than a Japanese princess currently marrying a “commoner,” or Hollywood movies so focused on the violent moments in history that they’ve now got actors shooting cinematographers.

I was sent a book called “The Art of Diplomacy: Fifty Years of Secret US-Japan Relations Revealed” by Stan Katz. There’s little if anything secret in it. It jumps around chronologically so much that I have no idea whether it’s about 50 years. It cites strange sources or none, has no endnotes, includes weirdly false information (such as the fabricated description of what’s in the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which could have been corrected in 2 minutes by reading the Kellogg-Briand Pact), and is written as a mixture of fact, opinion, and pseudo-eternal proverb (“It appears a contradiction, but to maintain peace, a nation doesn’t wish to be seen as weak or vulnerable.” Really? A nation? It has wishes? Which nation? In which brain?), but the topic is irresistible, apparently outrageously neglected, and the effort to bring it to the world’s attention in 2021 is highly admirable.

The U.S. Senate seems intent on bowing before Prince Biden and sending Rahm Emanuel off as U.S. Ambassador to Japan, with a mission of selling more weapons and building a greater threat of war on China. Prince Tokugawa was of a different era, that in which Joseph Grew, a sane and educated and experienced diplomat served — and it was actually a service — as U.S. Ambassador to Japan. When the Japanese military attacked and sank a U.S. ship in 1937, Tokugawa and Grew did everything they could to avoid war, and — whether through their efforts, or simply because Franklin Roosevelt didn’t want a war yet — peace was maintained. (Grew also warned the U.S. government about Pearl Harbor, though his warnings were ignored, and it’s now some sort of patriotic duty to continue ignoring them.)

Tokugawa died in June 1940, and by September Japan was aligned with Germany and Italy. How decisive Tokugawa’s death was in that development would require more research. Clearly, the struggle between hawks and doves in both the Japanese and U.S. governments had been inching toward a major hawk victory for years. Clearly we have been living through the same process again for years now, albeit with Japan and the United States united against China rather than China and the United States united against Japan. Stan Katz’s bizarre conclusion that the reigns of Obama and Abe in the U.S. and Japan would have been seen by Tokugawa as the fulfillment of his dreams misses the eradication of the Article 9 prohibition on war in the Japanese Constitution, the pivot to Asia, the militarization of every last inch of Okinawa, the new U.S. bases around the Pacific, the increased weapons sales, and the general normalization of hyper-militarization pushed by Abe and Obama — not to mention their successors.

Prince Iyesato Tokugawa (1863-1940) was heir to the Shoguns who ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868, educated at Eton, President of the upper house of the Japanese Parliament for 30 years, mentor and key advisor to Emperor Hirohito, world traveler and diplomat, key organizer of the Washington Naval Conference of 1921-1922 (the first international arms reduction conference, which opened on the day after Armistice Day, and had significant success, despite the U.S. spying on the Japanese delegation and the growing military industrial complex working the loopholes. Tokugawa was an outspoken advocate for peace for decades, and a leader in promoting the Rotary Club, the Red Cross, and countless cultural exchange initiatives, including the gift of the cherry trees to Washington D.C. and the development of a festival around them. Prince Tokugawa founded the first Japanese Symphony orchestra, created exhibits of Japanese art in the United States, established student exchange programs between the U.S. and Japan, and hosted a global conference on education, among much else. He sought a culture of peace while opposing the Armenian genocide and the rise of antisemitism. He was the keynote speaker at Rotary International’s 25th Anniversary Convention in 1930.

Even in his final years, even in the United States, Tokugawa spoke against the threats of war, advocating peace in terms that it’s hard to find any flaw in. On Armistice Day 1934 he joined with Nicholas Murray Butler in transmitting a global radio broadcast over CBS urging peace among the world’s “family of nations.” Tokugawa even tried meeting with William Randolph Hearst in an effort to tamp down on the pro-war “journalism” — with what success is not clear. China’s propagandists combined with weapon interests and FDR’s determination to find a way into the war in Europe were powerful forces.

The Los Angeles Times of March 21, 1934, on page 22, according to Katz, included a column — he doesn’t say by whom, but it should be here if you pay for it (I haven’t) — that stated:

“Prince Tokugawa speaks the language of enlightenment and understanding when he says there is no reason for the conflict between the United States and Japan. He is also probably correct in his statement that the majority of the Japanese people desire peace, as he is certainly correct in saying the majority of Americans desire it. It is jingoism in both countries and the fear they cause which are dangerous for peace. So far as his addresses serve to allay fear, Prince Tokugawa performs a distinct service by this tour. His report to his native land of what he saw here should overcome a good deal of jingoism. If the Hearst press here and its Japanese [equivalents] could be silenced by public opinion, all misunderstanding between the two nations would speedily disappear.”

The more things change . . . .