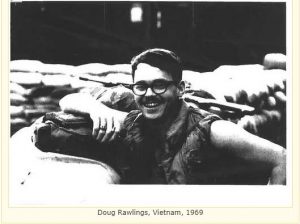

By Doug Rawlings

July 15, 2018

The recently announced Emmy nominations have generated new interest in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s 10-part documentary, “The Vietnam War,” nominated for an Emmy based on Episode 8, (April 1969 – May 1970), The History Of The World.

Vietnam veteran Doug Rawlings was in the Central Highlands with the 7/15th Army artillery that year and was later a founder of Veterans For Peace.

As each nightly episode of Burns/Novick series aired last fall, he wrote his insightful observations. Below is his analysis of the nominated eighth segment. For all his articles on this series, visit www.vietnamfulldisclosure.org.

EPISODE EIGHT: April 1969 to May 1970 “THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD”

Silence. That’s the overriding theme of this episode. Silence, as in Martin Luther King’s admonition that “our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” Does that not perfectly frame Nixon’s so-called “brilliant” maneuver of celebrating the amoral, even cowardly, silence of the majority of Americans in the face of this war’s immorality and in response to the righteous anger of young and old who raged against it? Nixon’s infamous “silent majority” speech kicks off this episode. To counter this political maneuver, one activist seared our TV screen last night with this placard: “To sin by silence when they should protest makes cowards of men —Abraham Lincoln.”

And then there is the silence of the filmmakers themselves, when it comes to the incredibly important GI resistance movement that rose up as Nixon tried to wind down the war. Where is that story? Passing references to disgruntled veterans voicing their anger, as important as those voices are, does not do it justice. We needed more. In an 18-hour series, one could expect time to adequately examine the courageous resistance waged by active-duty GIs to an unjust war they were ordered to fight and die for.

“Silence,” wrote Francis Bacon, “is the virtue of fools.” The persistent, unrelenting attempts, as with this documentary, to disguise the essential truth from the American people of the inhumane consequences of this country’s wars makes murderous fools of us all. Hats off, then, to those journalists, independent and corporate, who loaded onto choppers and dug in with the soldiers to capture their stories. Even with the repeated telling of the personal, which this series relies on heavily, the more universal truths began to seep out.

The military brass scrambling to silent voices like Ron Ridenhour’s for a year until the courageous journalist Seymour Hersch uncovered the My Lai and My Khe massacres – that kind of silence. American textbooks not celebrating the courage of Hugh Thompson and his crew as they dropped their chopper down between the civilians and the murderers led by Captain Medina and Lieutenant Calley – that kind of silence.

Almost intentionally blanketing this eerie moral silence are the sounds of bombs blasting away, M-60s rattling on, and the American and Vietnamese cities burning in the background.

At this point in their narrative the filmmakers provide a welcome sardonic voice to their portrayal of the war — suddenly, in late 1969 and early 1970, the Nixon crowd comes up with a marketing ploy — let’s “celebrate” the American POWs by making hundreds of thousands of POW bracelets for kids to wear and an equal number of the POW/MIA flags to fly over town halls across the land. One astute journalist says in the film, “It is almost as if the Vietnamese kidnapped 400 American pilots and the war is being fought to free them.”

“If Americans are convinced that their stiff-upper-lip brand of silence in the face of collective murder is the true face of patriotism, then we are condemned as a nation to follow the path of empires that preceded us.”

Even our so-called “terms of peace” – our promise to stop the bombing and withdraw all the invading soldiers – were dependent upon the total release of all American prisoners and the return of all the remains of killed GIs.

The hubris here is staggering. What of the over a million Vietnamese casualties of war? What about the Vietnamese prisoners tortured by U.S. forces or the tens of thousands maimed for life in South Vietnamese government “Tiger Cages?” What about their dead and missing? Should they not be accounted for as well? To this day, there are countless Vietnamese NVA and NLF soldiers whose remains are anonymously buried under triple-canopy jungle.

Yet reparations to the Vietnamese people after the war were one hundred percent contingent upon all American remains being found, and so, of course, we refused to pay anything. The Vietnamese can’t find the bombed and scattered body parts of literally hundreds of thousands of their own, let alone ours. No wonder the black POW/MIA flags still flutter.

If silence is to still rule the day, then there is no means for truth to wend its way into our consciousness. This is by design, of course. As Aeschylus warned us some one hundred generations ago, “Truth is the First Casualty of War.” If Americans are convinced that their stiff-upper-lip brand of silence in the face of collective murder is the true face of patriotism, then we are condemned as a nation to follow the path of empires that preceded us.

To break that crippling silence we must face facts. The difference between killing (as in self-defense or to rightfully defend our nation) and murder (as in slaughtering by bomb or by bullet defenseless, innocent civilians) needs to be held before us as a true measuring stick of our nation’s role in world history.

If this film were to be counted as some sort of success, then it would have to be measured by its contribution to breaking the sound of silence in our classrooms and town halls when old men and women try to throw away the lives of our children and grandchildren in yet another grand scheme called war. This exercise in reliving the past and calling forth old ghosts will be labeled another curious artifact if we don’t do something with it. If we don’t face our murderous ways.

-END-

Rawlings was drafted in 1968 and served with the 7/15th artillery in the central highlands of Viet Nam from July 1969 to August 1970. He retired in 2012 after teaching writing composition for 33 years at the high school and college levels in Maine. Email him at rawlings@maine.edu